Note: You can change font size, font face, and turn on dark mode by clicking the "A" icon tab in the Story Info Box.

You can temporarily switch back to a Classic Literotica® experience during our ongoing public Beta testing. Please consider leaving feedback on issues you experience or suggest improvements.

Click hereHere aboard, I cannot understand a word of instruction and counter command the sailors are calling out to one another. However, the bewildering array of ropes appear to be untied in the correct order, pulled and manipulated in mysterious ways and retied. All in presumably like fashion, with never an instruction needing to be shouted twice. We move, surprisingly quickly for such a large craft, through the still water and across the crowded harbour, full of other moving craft, each independent of the other, without collision. It is a bewildering marvel to behold.

Our attention is taken by a hue and cry from the shore. A body of Knights, heavily armed and above twenty in number, are dismounting from steaming horses and shaking their fists at us as we move away from the dock.

One or two even loosen a couple of arrows at us but we are three hundred yards from the wharves by now and the ill-aimed darts from their short cavalry bows fall a long way short. I thought of fetching my longbow, presently safe unstrung and bound in cloth against the damp sea air, but it would have been futile to respond by the time I had the weapon strung and ready for use.

Besides, the Lady Elinor is occupied in laughing at their antics, a spectacle to behold herself. She jumps up and down in her unconfined joy, making all sorts of hand gestures to them, no doubt some of them rather rude. She's not always the Lady she should be, I have noticed.

She calls to Hugh and I, "Look! It is the Count! We have beaten him to the boats! And the Captain says he cannot possibly sail for another 12 hours, we are a whole half day ahead of them!"

I look to where she is pointing. There indeed is the very Count, the only one still ahorse. While the others jump around, he is holding on tightly as his mount becomes jumpy at the excited crowd. As the horse turns, looking to flee inland, we can clearly see that he is riding high in the saddle atop a thick feather pillow!

We three laugh until the tears run down our faces, the sailors unaware of the reason for our mirth, but the ship starts to roll as we near the harbour exit, and ere long the ship crashes over the sea waves rolling in.

It is as if the ship is trying to shake us off its back like a donkey spooked by a family of hornets.

Hugh is the first of us landlubbers to lose his breakfast over the side, and I am not far behind him. Only Elinor stands aloof, laughing at our expense.

That is until we roll out of the harbour and the action of the vessel is more like an archimedes screw, hee-hawing forward and backwards and rolling from side to side and her face is suddenly even paler than pale. Soon she is next to me heaving like she was trying to haul a reluctant anchor up from the depths of her gizzards.

The whole of this day is burned on my memory like prize bull branding. The captain leaves us prone on the deck, retching as if our bodies think there's something still lying in a hidden corner of our stomachs. Something that it remembered eating on some forgotten feast day, while we were still at Sunday school, and keeps on prodding every corner of our guts until it finds it.

When a sudden icy squall passes us, a sailor throws a tarred sail over us for protection, but we are all past caring about our comforts in our utter misery.

All day long we are like this, and into the first part of the dark and starry night, when the wind suddenly drops and the motion of the ship slows to a small swell. Although the ship is hardly moving, I still feel I am moving just as I had been. My perception seems strangely out of kilter.

It is Hugh that stands up first, unsteady on his feet though he is. But he is standing, wet and shivering from head to foot. A sailor puts his arm around him and guides him to the forecastle.

I try to arise too, taking my time, and eventually sit up, wrapping my end of the old sail about me. I am shivering with cold but also at the shock of still being alive. I had given up my soul, to whoever wished to claim it first. I tap Lady Elinor on her ghostly hand, which is outside her covering sheet.

"Go 'way!" she says, weakly, adding an expletive. That I try to ignore. Where would a Lady learn a word like that?

Later she says. "I think I have died and the angels are holding me here while they count up my lies, before they decide where I go for eternity."

"Try and sit up if you can, my Lady. The ship is as calm as it will ever be and we must make the most of it and see if we can find some shelter, before we really perish from exposure."

"Can't move. Every muscle ... is like water, I think my guts have dissolved them all one by one and I have spat them out over the side into the ocean."

I laugh, and it starts me hiccoughing. I can't stop.

The sail next to me moves, it no longer covers a deceased person abandoned by debating angels. I fancy I see a head that is slightly lighter than the black sky behind. I hiccough again.

The head disappears and suddenly the sail jumps at me with a screeching "Yah!"

I fall flat on my back on the deck. "What was that?!" I cry.

"I was trying to frighten you, shock you into losing your hiccoughs. Did it work?"

I breath in and out. "Yes I think you have!"

"Good, let's go and get some bread and cheese, I'm hungry!"

No, she can't possibly be serious.

But I realise she is, both serious and hungry.

My stomach turns again.

14.

Welsh threat

(Will Archer, narrates)

I try my hardest to hold the town together, but more people fleeing the fighting around the city of Chester try to enter the town for protection. There is no sign of the Powys army in pursuit and I doubt they will come this far, but the refugees are not ready for persuasion from their convictions, their terror.

While there are pressures from without, the ferment within to escape the pestilence, is also a problem. Just as we thought the pestilence was waning, with fewer falling sick and with regular nursing to those remaining in their houses, we have had six deaths yesterday afternoon and two more overnight, including the merchant who took to the comforts of my bedchamber. The word of the fatalities has spread through the town and more people are wanting to leave, pressing that they are fit and not carrying the pestilence, but all who know me, know that I will not, cannot take the chance.

I bend an arrow onto my trusty bow this morning for the first time in a week, I have had no time to practice my archery skills, but at this range my dart would pass through three men at full draw.

And use it I will.

I stand facing the head of the protesting townsfolk in the Market Square. I have a handful of fit men at arms, too few who could be spared from the pickets, including my clerk Jack Moor, just risen from his sickbed this morning, his fever broken but his body too weak yet to wield a sword. His hand rests on his dagger and he looks mean.

The leaders of this rebellion are mostly silent, only the butcher Owain, who was once of Chester, with the bloodiest tools of his trade in his hands, is moved enough by his former friends and neighbours to speak up.

"Let the Chester folk in and let us fit men out while we still can. We be not sick, yet if we tarry, surely it is Almighty God that has inflicted this plague upon us as a warning to leave this place. If we stay, surely we will suffer too."

I remove my face mask to speak, raising my voice so all may hear on both sides of the divide. "You can leave this place whenever you choose, but it will be in a pine box if you catch the devil's breath, or a pauper's shroud if you do not disperse. Let there be no confusion, let all hear and understand. Be sure that I will take the ultimate sanction on anyone willing to risk passing this pestilence to the rest of the shire and I will surely have the town confiscate your every possession, leaving you and your families as paupers, if you continue to defy martial law."

I cannot lay it on any thicker than show them that I mean business. To the death if need be. The citizens of this town need to be aware that I have to make the best decisions both for them and the rest of the people in this shire. If I was an ordinary man, I might have been tempted to sneak off out into the countryside myself to escape this pestilence, but I am a man with responsibilities and I will do my duty even if I have to die in the process.

The crowd is silent.

"Go back to your homes and wait this out. If you have no food or drink, come to the square at noon and mid-afternoon, when there will be fresh vegetable and fruit gruel and bread from the bakery, as well as ale and fresh well water from Oaklea ready to dole out fairly and squarely."

Now the crowd is noisy with discussions but they disperse and make their way back to their homes.

15.

Grateful

(Lady Alwen Archer of Oaklea narrates)

This morning I am able to send four carts containing barrels of ale and water to Bartown. My coopers, maltsters and brewsters are working flat out, with every brew tun full to the brim with fermenting ale. The empty barrels returned yesterday were opened, scalded and rinsed out. Then they were refilled and loaded ready first thing this morning. I even sent a cart out yesterday to collect empty barrels from other ale houses, rather than leave them until their next delivery day.

I feel good in myself now, although I did feel so tired and pained somewhat yesterday. I am filled with energy today.

I send another letter to William with the first dray out, which should arrive before noon. I know he cannot reply to me, as we have no idea of the risk involved in any object upon which the pestilence has settled and fermented.

There is talk of war in Chester, that the Prince of Powys has sacked the city in reprisal for past transgressions. That is the word the draymen bring from Bartown. No one but the refugees believe it is a Welch invasion, the Welch are too few and the barons without too strong. Those that run from Chester tried to enter Bartown, but have been moved on. Some come to the hamlet of Brey, where there is a Cluniac monastery, which is well provided for, and will offer succour while they may.

More people on the roads mean delays getting to the town and back. And the more desperate people are the more my deliveries and my draymen are in danger. If only Henry, Robin and Hugh were here, they could have ridden with the draymen to deter and protect from the malcontent.

16.

Confession

(Robin of Oaklea narrates)

The wind changes during the night, though from where I lay, unable to move in the forecastle, I cannot see from which direction. Mercifully, the ship seems to be moving more forcefully, and with purpose, through the water.

Annoyingly, both Elinor and Hugh appear to have recovered fully from the bout of seasickness, as they are not with me in the forecastle, where we all collapsed late yesterday.

They no doubt cavort on deck without a care in the world, while I languish here, my body still trying to scour my insides through repeated attempts to bring anything still residing there to my mouth and nose. These spasms do nought to elevate any residue, other than fatigue me to the point of exhaustion, wishing for death's promised release.

I confess that I have mixed feelings about the existence of an eternal world after we're spent in this one. My sister and adopted stepmother Alwen swears that the Bible holds the truth and the manner in which we should live for our reward in the next life. I was in Father Andrew's Sunday School since I was old enough to talk, listen and understand. And still I was confused by what I learned. The Priest says that you shouldn't go by what your eyes tell you the words on the page mean, but to have faith you must believe in the teaching behind the words, even if it makes no physical sense.

Now my father is a practical man, whose vision of targets and feel for air and wind and distance, rely solely on his physical senses. He has seen almost as much of the world as the Priest, and he tells me straight that for him there is nothing to believe in other than yourself. Live a life with respect for others, and for no reward other than your own self respect. If you have no faith in your own ability to be strong, to be able to protect your friends and family, then you are lost; and being lost is like being in Hell.

But he also tells me to go down my own path, to decided for myself what is right for me to believe. Because, if he is right, then Father Andrew and Alwen are wrong, and that doesn't sit right with him either.

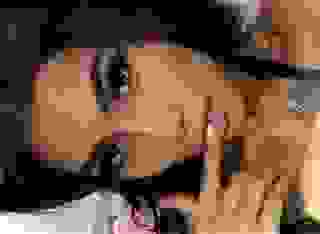

I take the time lying there to think about Elinor, the Lady Elinor. What do I think of her? On the surface such answers are easy, she is pleasing to the eye. I think she looks stunning and beautiful, of course. Anyone would believe that. But what is she like as a person? This is an example of having faith in a belief that you cannot see. Is she a good person, or is she playing an act?

It is something I cannot answer. Do I go with Alwen and Father Andrew's way of faith in what I feel, or the practical side that my father prefers? Sometimes I just can't stop looking at her. The hair, of course, is such a vibrant rich dark brown with hints of red that is arresting and that there is so much of it, especially when the wind gets in and tosses it in all directions.

Her eyes are like gems. I have seen such stones, worn by high ladies passing through and staying at the inn, but those stones were cold, dead, while these gemstones that make up Elinor's eyes are alive and all the more brilliant for that. In her everyday clothes she could past for a small boy, but in that blue silk bliaut, that she has sinced parted with, she looked like an angel.

She plays the high born lady so well, but sometimes she lets that mask slip and she could as easily be one of the serving girls that we have at Oaklea Inn.

Perhaps it is this place she comes from that is so small that there are no discernible boundaries between Ladies and Servants? We are much more free and easy in Oaklea than they are in Bartown, but there is still a clear difference even if we do hold a sense of respect on both sides.

It is a gradual feeling of getting better that brightens me, makes me attempt to sit up. I am weak, terribly weak, and my throat is raw from the coating of burning stomach juices. Now that I feel better, I need to wash and drink and, at some point when I feel more refreshed, something to eat.

But not yet, even the thought of ... no, I cannot think the word, before nausea returns.

I sit up and, although my head is still spinning back and forth like a weaver's shuttlecock, I no longer feel wretchedly sick. I stand and stagger out into the fresh air and the afternoon sunshine. I can see from the low sun that we are in the middle of the afternoon, and still heading east-south-east. I connot look the way we have come, the low sun burns my eyes.

"Ah, you are up, at long last!"

I turn to the Lady, and I instantly feel my face reddening, looking guilty, as if she has read my mind and aware that she has been constantly in my thoughts since I awoke from my stupor.

"That's better, at last you have some colour in your cheeks," she says, as cheerful as a sunny day, "come, Master Robin, you must drink a full cup of water, two if you can. It will settle your stomach and banish the ache in your head, although that will take but a little while."

She passes me a rough pottery cup of water, which I sip cautiously, awaiting the inevitable gagging, followed by vomiting, but a moment passes without adverse reaction, so I drain the cup.

"Thank you, my Lady, thank you. I should be serving you, I must apolo—"

"Don't apologise, Robin, you have served me better than I could ever have imagined. Look how far you have got me since you found me abandoned in the wood! You are more a knight in shining armour than any archer's apprentice."

She completed poring a fresh cup of water from an earthenware jug and returned it to me.

"And you, my Lady Elinor, you are unlike any Lady I know."

"What do you mean?" she asks in a small voice, again unlike any Lady I know, other than my dear modest sister, Alwen. And Alwen has only been a lady for a little over a year, when my father was given the title by the late Lord of the Manor, by adopting Will as his son and heir.

"I mean no offence, my Lady, only that you are more like my sister, who is as gracious as any lady, but who runs our inn as if all the serving maids are family and friends rather than servants or slaves."

She is silent, her face pained, looking down at the deck of the cabin. I take her silence and expression as signs that I have insulted her, where it is not my place so to do.

"Forgive me Lady Elinor, I did not mean what I said as any criticism of the way you deport yourself, nor that I was especially spying on your private actions. My intention was a compliment, that you have a common touch. So when you feel you don't have to put on an act as a Lady, you can be as humble as a serving maid. I find it endearing."

She looks up, biting her lip, struggling to say something but unsure how or what to say.

"How long has your sister been a Lady?" She asks with a tremble in her voice.

"Not long, just over a year, when my father was knighted."

"But how would that make your father's daughter a Lady? You are not a knight through your father."

"My sister is my father's wife."

She looked shocked, "Your father married your sister, you are adopted?"

"No," I laugh, "in a way that would be simple, but my family is complicated."

"Mine is too," she says in her small voice again, "so how complicated?"

"My father is my natural father and my half-sister is also my step mother, as we share the same mother, but please say nothing to Hugh. He doesn't know, and I would rather keep it unknown."

"Yet you tell me, a stranger?"

"We are temporary acquaintances, my Lady, ships that pass in the night, like this one. My chivalric obligation to you is nearly over and I must of necessity return to my family."

"Yes, of course you must, as soon as we are done. But will you ensure I reach the sign of the Red Hand safely?" she asked, "Though we have left the Count well behind, he has lands here presently seized by the Count of Flanders, and has friends who may stop me reaching my destination."

"I will serve you until you reach the bank. I confess that I do know the proprietess, Jessica, previously of Lincoln, the daughter of Jacob of York and London."

"You know this bank and yet didn't say anything when I mentioned my destination yesterday?"

"I was concerned, early on, that you were not telling me all the truth and so ... I kept my secrets too."

"Secrets," she muses, "we all have secrets, Robin."

"And what exactly are yours?"

"All right, you asked, and I will tell. I confess that I am not Lady Elinor at all, but her maid of the chamber, Jane," she looks at me defiantly, chin in the air.

"What?!" I am no longer weak and sickly, I stand up straight, the blood in my veins pumps quickly.

"If I may explain?"

"Please do, er, Mistress Jane is it?

"Yes, Jane Elliott. You say your step mother has only been a Lady for a year, before that an innkeeper?"

"Aye, though she still keeps the inn."

"So does my mother, 'The Three Horseshoes Inn' at Pitstone. I, Robin of Oaklea, have only been a Lady for a week!"

"So who is the Lady Elinor? Where is she?"

"She didn't want to marry the Count. My lady was in love with another and has since eloped with him to London to marry. I took her place at the church ceremony, to delay the chase. But I found I was unable to fully sacrifice myself to such an odious man as my Lady's new husband."

"However did you manage such deception?"

"It was easy, this was an arranged marriage, and they had never met. Lady Elinor, or me, her maid, we could have been anyone, anyone who could be convincing enough, after all he was expecting a maid with rough edges, a titled lady, yes, but also the daughter of a barkeeper. We could not marry at Pitstone, where we were both known, and it would have been impossible to carry on the charades. However, he was happy to marry at Wellock Brigga, where he knew the Lord of the Manor and has been staying there these last few months since losing his lands in Flanders."