- Lesbian Sex

- Oyster River

- Page 2

Note: You can change font size, font face, and turn on dark mode by clicking the "A" icon tab in the Story Info Box.

You can temporarily switch back to a Classic Literotica® experience during our ongoing public Beta testing. Please consider leaving feedback on issues you experience or suggest improvements.

Click hereA large, sparkling nest of condominiums sat on the right bank. There was a small marina in front of it, but only a handful of the slips were occupied. The church steeples of town came into view, and then the town itself. They passed Seaview Park, and the outdoor deck of Mariner's Restaurant. There was a line of big waterfront houses and then the downtown itself. Many of the buildings along Main Street hugged the shore. Some had upstairs apartments, with balconies hanging above the water.

They entered the wider harbor. It was dotted with bobbing white mooring markers, most of them still empty, waiting for their summer occupants to arrive. Pop weaved through them easily, and entered the main channel. He pressed the throttle and they sped up, quickly passing the town landing, the shipyard and Dean's Lobster Wharf.

"You sure we are good on bait?" Pop called over his shoulder.

"Bagged it on the way in yesterday," Michelle told him. "We got more than we need for the string."

As they cleared the harbor, Michele watched the town shrink behind them. It always looks so small from out here, she thought. There had been a time when it had seemed the grandest city on earth.

They rounded Otter Head and entered the greater expanse of the Gulf of Maine. The perpetual fog bank was no more than a couple of miles offshore. It blocked the rising sun, coloring the sea a slate gray.

"Northern string today, Pop," Michelle said.

"You don't have to remind me every time," he grumbled, "Just 'cause I mixed it up once."

Michelle ignored his complaint. It had been more than once.

The Roberts family had been lobstering in the Gulf since before the turn of the last century. Like his ancestors in all those generations, Michelle's father had been working three strings of traps, one string each day, six days a week, every week, since he had been a boy. It was a simple matter to maintain the daily rotation, but lately Michelle noticed that he would sometimes get confused.

One thing Pop never seemed to get confused about was the location of the traps themselves. The coast was no more than a dark line on the western horizon when he pulled alongside the first familiar red and green buoy. When she was a little girl, Michelle thought they looked like Christmas ornaments floating in the water.

She picked up her gaff and as soon as they drew near enough, she thrust it under the buoy and then, in one smooth, quick motion, hooked the trap line, pulled it from the water and draped it over the wheel of the hauler. She flipped the hauler's switch and the pulley began to turn. The line grew taut as it rose, dripping, from the water. When the trap emerged she grabbed it in both gloved hands and lifted it over the rail. There were four lobsters inside. She flipped open the lid and pulled one out. It was obviously too small, so she tossed it back into the ocean.

"Couple good bugs here," she said, "Look to be near two pounders. " She dropped the two big ones into the hold. The third was borderline. She measured it, saw it was good, and tossed it in as well.

"Good start to the day," Pop said over his shoulder, "Now, watch your feet, honey."

Every day, when she dropped the first trap, he reminded her to never move her feet when there was a trap on deck; never risk getting tangled in the rope. It was one of his absolute rules. She had broken it once, when she was thirteen, and he had given her the worst ass whipping of her life. She had never forgotten it since.

Michelle dropped a bait bag in the trap, closed it and unhooked the line.

"Good to go, Pop," she said, and dropped it over the side. She watched it sink beneath the surface. One down, she thought, ninety nine to go.

Michelle could not keep track of the count in her head, but somehow Pop always knew how many traps they had checked. The sun was high in the sky when he told her, "That's fifty."

"Do you want to to have lunch, or haul a few more first?" she asked.

He stepped back from the wheel and looked into the hold. "I don't know, don't it look a smidge light to you?"

"Yeah, a little bit."

"Let's keep her going a while."

She could never understand why he thought that the sooner they checked the traps, the more lobsters they would find, but there was no use in arguing the point with him. They hauled another ten, then he cut the engine.

Michelle fetched the cooler from where she had stashed it beneath the seat. She opened it and took out two of the sandwiches and a bottle of water and handed them to her father.

It had gotten hot in the sun, so she pulled off her sweater. The front of it was soaked. She held it over the side and wrung it out, then tied the sleeves around one of the rear cleats to dry. She sat down on the stern bench to eat her sandwich.

"Look at that big bastard," her father said.

A half mile off their port side, she saw a mammoth luxury yacht.

"Eighty footer?" she asked.

"Looks about right." He seemed lost in thought for a moment then said, "I remember when you used to talk about maybe getting a job crewin' one of those big boys."

"Yeah," she said, shaking her head, "That was before I realized what it would be like dealing with rich folks all day long."

"Well, I still ain't sure it's the best thing for you to be out here all day spending your time with your old man, either."

"Come on, Pop, don't start on that again. If I was your son instead of your daughter, you wouldn't say that. You'd assume that I was going to carry on in the family business."

"Can't tell you you're wrong, honey," he said, "But it ain't so much that you're a girl, but you're a certain kind of girl."

"What does that mean?"

"You know, honey, when you first told me, it sort of felt like a relief. I think I knew before you did. You never had no use for boys. And I never gave a damn if you wanted to have a boyfriend or a girlfriend. Did I ever tell you that my Aunt Daphne lived her whole life with what we called her female companion?"

"You told me, Pop."

"Of course, I didn't want my little girl to be all tore up inside about who she was or if I thought it was all right, and that seems to have worked out."

"I've always known that."

"But the one thing that bothered me, and does to this day, was thinking of you being lonely. I know how hard that hurts. Known it since your mom passed."

A trio of gulls circled overhead. Michelle watched them for a few minutes.

"Sonsabitchs want your sandwich," her father said.

She looked at him and said "I am lonely, Pop."

"I've told you before, honey. I could hire a sternman, maybe not one as good as you, but one that'll do the job. You could move down to Portland and sign on with a boat there, or out of Yarmouth. You could meet more girls your own age, maybe find somebody special."

Michelle finished her sandwich and stood up. "The problem with that, Pop, is there ain't nothing special about me."

"Aw, horseshit."

"Besides, if I move down to Portland, who's gonna take care of you?"

"I don't need no one to baby me," he grumbled.

Michelle closed the cooler and stowed it away. "Let's get back to it," she said.

Pop started the engine, and looked toward the yacht, shrinking in the distance. "Guess the summer folk will be crawling all over our backsides pretty soon," he said. He looked at Michelle for a moment. "Maybe you'll meet somebody nice this summer, somebody that will treat you right."

"I don't know, Pop. I guess we'll see."

"What about that Sharon? Is she coming up this summer?"

"No."

"I liked her."

Michelle picked up her gaff and looked out at the next buoy. "Yeah, Pop. I did too."

Laurel and Michelle, Summer 2004

The summer's worst heat wave settled in during the last week of July. Each day the temperature would rise from late morning through the afternoon, then, like a miracle, around three o'clock, the sea breeze would begin to flow and provide cool relief.

"Why does it do that?" Laurel asked her father as they ate supper on the deck.

"Warm air rises," he explained, "As the sun beats down all day the land gets hotter and the water doesn't. So the air over the land rises and the cool sea air flows in."

"That makes sense," Laurel said. She leaned back in her chair with her arms spread wide, closed her eyes and enjoyed the feeling of the breeze. After a moment, she inhaled deeply, let it out and sat up, feeling energized for the first time in days.

"Now that it's cooled off, I think I'll take a walk around town," she said.

"You ought to walk by the water, it'll be even cooler there," her mother advised.

Laurel looked out toward the harbor. "I don't know," she said, "Is it safe walking around down there?"

"Of course it is," her father said, "People go down there all the time to buy seafood at the fish markets. Sometimes, they buy right off the boat."

"Yeah, that could be interesting. It's the one part of town I haven't been to."

Laurel found the harbor to be much more interesting than she had expected. Her mother had been right, it was much cooler along the waterfront. She walked down the road to the town landing, where she watched as a man and two teenage boys loaded a small motorboat on a trailer.

At the little harbormaster shack she stopped and looked at a bulletin board of announcements. Some were official notifications; hours of operation, prices for boat fuel, a warning against interfering with the migration of right whales. There were community announcements as well. There was a bean supper scheduled a the Methodist Church and an auction at the Masons Lodge.

From the harbormasters office she wandered through the shipyard. There were several boats standing on jacks. She'd seen them from the cottage, but had no idea now big they were until she saw them up close.

She walked past a large pile of lobster traps and stepped on to the boardwalk that ran along a portion of the shore. As she strolled down it, looking out at the boats bobbing at their moorings, she saw a large, long necked bird swimming just a few yards in front of her. She wondered what it was. Perhaps if she took a picture of it, her father might be able to identify it. But before she could get her phone from her pocket, the bird dived under the water. She looked around and saw it resurface further down, near the end of the boardwalk. She followed it but before she got near, it disappeared beneath the surface again.

When she did not see it reemerge, she looked around the harbor from her vantage point on the boardwalk. She had a good view of Dean's Lobster Wharf, just ahead of her on the shore.

The wharf itself was built of rough wooden planks and didn't look very safe to Laurel. In several places, she could see the water between the boards. It stood in front of a large red building that looked like a warehouse. There was a door near the right side of the building with a sign that read "Retail Sales," but most of the front wall was taken up by a pair of large overhead doors. Lobster buoys in a rainbow of color combinations hung from the walls. Next to the building was another massive pile of traps.

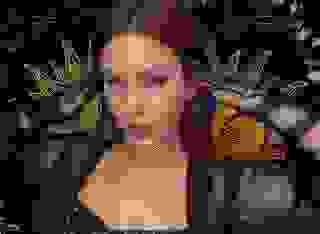

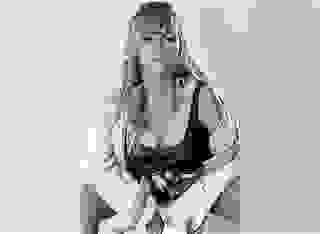

She heard the sound of a motor approaching and looked up to see a small boat moving towards the wharf. That must be Santa's boat, she chuckled to herself when it grew close enough that she could discern the red and green stripes that circled its hull. The boat slowed and began to turn as it got closer to the wharf and Laurel noticed that someone was standing on the rail. That doesn't look safe either, she thought. She watched as the boat glided in reverse towards the wharf. Laurel saw that the person on the rail was a young woman, her own age or maybe a few years older. She couldn't see her face clearly, her long dark hair was blowing across it in the breeze. She was wearing a red t-shirt that clung to her body, it looked like it was soaking wet. She had on a pair of denim cut offs and ugly green rubber boots that came up nearly to her knees.

When the side of the boat was within a foot or so of the wharf she stepped over the gap as if she were walking from room to room in her house. Without breaking stride, she went into the big red building. The boat engine quieted to a purr. The name Carol Anne was painted across the stern. She wondered if that was the girl's name. A scrawny older man emerged from inside the boat's little cabin and stood on deck with his hands on his hips. That must be her father, Laurel thought.

The girl came out of the building pushing a long low wooden cart, holding a half dozen blue plastic bins. Laurel could see her face clearly now. She was pretty, but there was a weariness on her face. Laurel imagined how hard it must be working on a lobster boat all day.

The girl pushed the cart to the edge of the wharf, parking it parallel to the boat. She hopped down to the deck, and she and the man began lifting cartons of live lobsters from the boat and dumping them into the plastic bins on the cart. There were hundreds of them. At one point the girl stopped, picked a lobster up and examined it closely, then casually flipped it over her shoulder into to the water.

Laurel felt guilty spying on them, but he couldn't take her eyes off the girl. Yes, she was pretty and she had a nice fit figure, but it was not her appearance as much as the way she moved, a gracefulness even in doing such taxing work, that really drew Laurel's eyes to her.

They finished transferring the lobsters to the bins and the girl climbed out of the boat and pushed the cart toward the big doors. It was obviously very heavy and even from a distance, Laurel could see the muscles in her arms and legs straining. She was surprised to realize how attractive she found the sight of them.

The man sat on the boat rail, his head drooping below his shoulders. Laura felt great sympathy for him, he looked so tired.

The girl came out of the building a few minutes later. In one hand she was carrying a five gallon green plastic bucket. There was a piece of paper in the other hand. She set the bucket down on the edge of the wharf, jumped on board and handed the paper to the man. Payment for their lobsters, Laura guessed. She took hold of the bucket and lifted it down to the deck. The man got up and went back to the wheel. The engine growled and the girl picked up a long pole and used it to push them away from the wharf. They turned and moved away from the shore, then turned again and headed up river.

****

The girl was there again, for the third day in a row. Michelle had noticed her the first day, standing at the end of the shipyard's boardwalk, but hadn't thought anything of it. Just another tourist, she assumed, watching the boats come and go. She might not have paid any attention to her on the second day either, but her father had noticed her and grumbled his usual complaint.

"Folks from away like to come down here and gawk at us like we are monkeys in the friggin' zoo," he said.

Michelle glanced over from sorting the lobsters to see who he was talking about, and got a good look at the girl. She was really cute, she noticed, her delicate features framed by honey blonde hair in what Michelle thought was called a pixie cut.

Michelle stood up straight and looked right at the girl. Their eyes met for a moment and Michelle waved to her. The girl raised her hand, but then dropped it and looked away.

Michelle shrugged and went back to work. Now, the girl was there again, standing in the same spot. Michelle pretended not to see her but as they offloaded their haul, she would surreptitiously glance in the direction of the boardwalk. There was no doubt about it, the girl was watching her.

When the cart was loaded, Michelle stepped on to the wharf.

"Give me a hand," her father said, "I need to use the head wicked bad."

She reached out and took his hand, and helped him up.

"I won't be but a minute," he said as they pushed the cart toward the double doors. Michelle knew better. Not only would he be longer than that in the bathroom, once he got inside the building, he would start shooting the breeze with the Dean brothers and whatever lobstermen were about.

While he walked off toward the bathroom, Michelle pushed the cart over to the weigh station.

Butchie Dean was behind the scales. He was a rotund man, with a scruffy red beard and crew cut. He looked at Michelle over the top of his thick glasses.

"Looks like a wicked good haul," he said, peering down into the bins on the cart.

"Fair day," Michelle said, nodding. She loaded the lobsters on to the scales. At the last moment, while Butchie was totaling them up, she grabbed one out of the nearest bin.

"You got some bags there, Butchie?" she asked.

He reached under the counter, pulled out a worn plastic shopping bag and handed it to her. She lifted three more lobsters off the scales and dropped them into the bag.

"Takin' your supper home with you?" Butchie asked.

"Giving a few to a friend."

He handed her the invoice and check.

"Tell ya what, Butchie," she said, "Why don't you give that to me dad when he comes out of the john?"

She walked out to the wharf. The girl was still standing at the end of the boardwalk. She headed straight toward her, the lobsters wiggling in the bag.

When the girl and her father had gone into the building, Laurel's attention had shifted to a two masted sailboat that was gliding into the harbor. She heard the footsteps in the gravel parking lot, but didn't look up until she heard someone say "Hey."

She turned, and the boat girl was standing right in front of her, holding a bag. The bag was moving.

"My name is Michelle," the girl said, "I seen you been down here a few times, I thought you might like some lobsters." She held out the bag.

Laurel hesitated before accepting it. "They're still alive?"

"Of course they are."

"How much?"

"I'm not trying to sell them. They are a 'nice to meet you' gift."

"Oh." Laurel blushed. "Well, um, nice to meet you." She took the bag, holding it cautiously away from her body.

"You didn't tell me your name."

"Laurel."

"That's pretty. I like that."

"Thanks. Can I set this bag down?"

"Not unless you want them to crawl away," Michelle said. She reached over and took the bag back. "I'll hold them for now."

"I thought maybe your name was Carol Anne, like the boat."

"No, it's named after my great grandmother."

"Wow. So it was your great grandfather's boat? Your family has been in the lobster business that long?"

"Longer than that," Michelle replied, "I'm the eighth generation. "And it was my grandfather's boat. My great grandfather's boat was called Suzette. She got stove up on the rocks at Halibut Point."

"Oh my god, what happened?"

"He got tangled in a line and went overboard."

"That's horrible!"

"Yeah, you got to be careful. You get that line wrapped around your leg or something and you throw that forty pound trap over, you're going with it."

"How do they know what happened?"

"Well, some of the other lobstermen found him when they went out to haul his traps until my grandfather could get a new boat. That's the way it is. Lobstermen are tough competitors, but we stick together when one of us is in trouble."

"You call yourself a lobsterman?"

"Yeah, lobster woman sounds silly. I don't mess around with that kind of foolishness."

"So, your grandfather got a new boat and named it after his mother?"

"That's the tradition."

"You would think they would name them after their wives."

Michelle shook her head. "Nope, never."

"Why not?"

"Because wives come and go, but your mother is your mother forever."

There was a sharp whistle. Michelle looked over her shoulder. "That's Pop," she said, "I gotta go. But if you come back, maybe we can hang out."

Laurel hesitated, then nodded and said, "Yeah, sure."

"Good, because you owe me," Michelle said as she walked away.